The Sacred Stage: Reimagining Entertainment, Ministry, and Art in the Life of the Christian Artist

In an age where screens flicker with endless content, where music floods our ears and stories shape our imaginations, the concept of entertainment has become both ubiquitous and suspect—especially within the walls of the church. For many believers, particularly Christian performing artists, the word carries a subtle stigma: Is it spiritual? Is it ministry? Or is it just… entertainment? This tension is not new, but it has intensified in a culture that often separates the sacred from the aesthetic, the holy from the enjoyable. Yet beneath the surface of this debate lies a deeper truth—one that speaks to the very nature of God, the design of the human soul, and the redemptive purpose of art.

To understand the role of entertainment in the Christian life, we must first return to its essence—not as distraction or indulgence, but as a profound expression of what it means to be human, created in the image of a God who delights in beauty, rhythm, and story.

The Meaning and Psychology of Entertainment

At its core, entertainment is any experience designed to engage, delight, or captivate the human spirit. It arises from our innate desire for joy, connection, and meaning. From the laughter of children at play to the hush of a concert hall, entertainment is woven into the fabric of human experience. But its significance extends far beyond mere amusement. Psychologically, entertainment serves as a vital mechanism for emotional regulation, cognitive engagement, and social bonding.

Neuroscience reveals that moments of joy, music, and storytelling trigger the release of dopamine and oxytocin—chemicals associated with pleasure, trust, and connection. Laughter reduces cortisol, the stress hormone; music soothes anxiety; narrative immersion allows us to process complex emotions in safe environments. These are not incidental effects. They reflect a deeper design: God created us with hearts that need beauty, rhythm, and story to flourish.

The human soul, far from being a purely rational or spiritual entity, is a holistic union of body, mind, and spirit—capable of awe, wonder, and deep emotional resonance. When we encounter a powerful film, a moving symphony, or a dance that seems to defy gravity, something within us stirs. We feel, perhaps for a moment, a glimpse of transcendence. This is not escapism; it is reconnection—with ourselves, with others, and with the divine.

The Psalms, perhaps the most artistic book in Scripture, are filled with calls to worship through music, dance, and poetic imagery. “Praise him with the sounding of the trumpet, praise him with the harp and lyre, praise him with timbrel and dancing, praise him with the strings and pipe” (Psalm 150:3–4). Here, worship is not silent or somber—it is embodied, rhythmic, and celebratory. The ancient Israelites did not separate art from devotion; they fused them. Their worship was, in the best sense, entertaining—not to amuse, but to awaken the soul to the majesty of God.

The Role of Entertainment in the Human Soul

Entertainment, at its highest form, does not numb the soul—it nourishes it. It provides what theologian David Taylor calls “a foretaste of the feast to come.” In a world fractured by pain, injustice, and isolation, beauty becomes a form of resistance—a quiet protest against despair. A well-told story can restore hope; a melody can carry someone through grief; a dance can express what words cannot.

This is why entertainment is not a luxury, but a necessity. Just as the body needs food and the mind needs truth, the soul needs beauty. The prophet Isaiah speaks of God replacing mourning with “the oil of joy” and despair with “a garment of praise” (Isaiah 61:3). These are not abstract metaphors. They are embodied realities—oil that anoints, garments that are worn, songs that are sung. God does not merely forgive our sins; He restores our capacity for delight.

Jesus Himself understood this. He did not speak only in dry propositions. He told parables—stories rich with imagery, humor, and surprise. He attended weddings and feasts. He wept at Lazarus’ tomb and laughed with children. His presence was compelling, magnetic, engaging. Crowds followed Him not because He was boring, but because He was alive—and His life radiated joy, wisdom, and power.

To deny the soul its need for entertainment is to deny the fullness of human flourishing. We were not made for mere survival. We were made for abundant life (John 10:10)—a life that includes laughter, creativity, and celebration.

The Trichotomy of Ministry, Worship, and Entertainment

This brings us to the heart of the dilemma faced by so many Christian artists: Is my art “ministry,” or is it just entertainment? Must I choose between spiritual integrity and artistic excellence? Between preaching and performing?

The false dichotomy between “ministry” and “entertainment” is a product of a dualistic theology that elevates the spiritual over the physical, the sacred over the cultural. But Scripture knows no such divide. In the beginning, God looked at His creation—not just the soul, but the physical world—and declared it “very good” (Genesis 1:31). He filled the earth with color, sound, scent, and rhythm. He gave humans the capacity to craft, compose, and create.

Bezalel, filled with the Spirit of God, was called not to preach, but to design artistic works in gold, blue, purple, and fine linen for the tabernacle (Exodus 31:3–5). His art was not “secular.” It was sacred. David, a man after God’s own heart, danced before the Ark with abandon, wearing a linen ephod, “leaping and dancing before the Lord” (2 Samuel 6:14). Was he “entertaining” the crowd? Perhaps. But he was also worshiping with his whole being—body, soul, and spirit.

Worship, then, is not confined to four spiritual walls or a set of doctrinal statements. It is the posture of a heart surrendered to God, expressed through every dimension of life. When a Christian musician writes a song that stirs the emotions, when a dancer moves with grace, when a poet captures the ache of longing—this is worship. Not because it is “religious,” but because it is offered to God and flows from a life of devotion.

Ministry, too, must be reimagined. It is not limited to altar calls or evangelistic tracts. Ministry happens when a song helps someone feel seen. When a story gives voice to the voiceless. When a painting captures the sorrow of the world and the hope of redemption. Jesus ministered not only through sermons, but through miracles, parables, meals, and touch. His entire life was a performance of the Kingdom—dynamic, embodied, and deeply engaging.

To say that Christian artists must choose between “ministering” and “entertaining” is to misunderstand both. True ministry engages. True worship delights. And true art reveals.

Toward a Theology of Redemptive Art

Christian artists are not called to produce propaganda or religious kitsch. They are called to be cultivators of beauty, stewards of imagination, and ambassadors of grace. Their work is not less spiritual because it is enjoyable. In fact, it may be more effective because it is.

Consider the parable of the sower (Matthew 13). The seed of the Word falls on different soils. But notice: Jesus does not deliver this truth in a lecture. He tells a story—one that captures attention, sparks curiosity, and lingers in the mind. He entertains in order to transform. The same principle applies today. A sermon may inform the mind, but a song may capture the heart. A painting may bypass defenses and speak directly to the soul.

The early church understood this. They sang hymns (Ephesians 5:19), celebrated feasts, and used music and art in worship. The great cathedrals of Europe were not built to be museums, but to point upward—to awaken awe and wonder at the majesty of God. Artists like Bach, Michelangelo, and Donne did not see their work as separate from their faith. For them, creativity was an act of worship.

Today, Christian artists stand at a crossroads. They can shrink back, afraid of being labeled “worldly,” or they can step forward, confident that their gifts are holy, their calling divine, and their art redemptive.

A Word to the Artist

If you are a Christian artist wrestling with this tension, hear this: You are not less spiritual because your music has a beat, your poetry uses metaphor, or your performance draws applause. You are not called to make art that is safe, but art that is true. Not art that avoids culture, but art that redeems it.

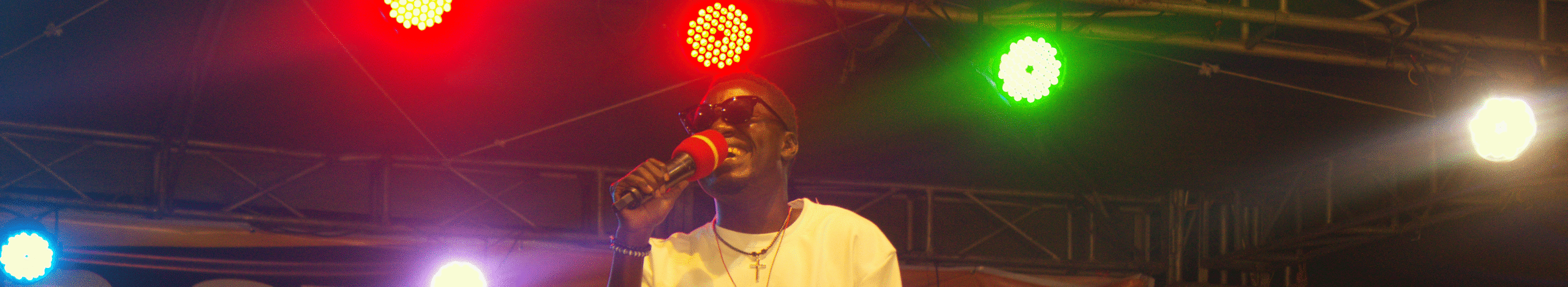

Your stage is a sanctuary. Your studio is a chapel. Your creativity is a form of stewardship. When you write, paint, sing, or dance, you are participating in the ongoing work of shalom—the restoration of all things. You are not merely entertaining. You are inviting people into wonder, into healing, into the presence of God.

Let your art be excellent. Let it be engaging. Let it be beautiful. And let it all be for Him.

As the Psalmist declares, “Let everything that has breath praise the Lord” (Psalm 150:6). That includes your voice, your hands, your imagination. Every note, every brushstroke, every word—let it rise as an offering.

For in the end, the greatest art does not choose between worship and entertainment.

It transcends the divide—

and becomes, in its own way,

a living act of worship.